The corpse may seem to be the most useless of items, nothing more than the star attraction at an overpriced funeral. But there are no limits on the human imagination. Faced with a dead body, the true optimist sees not a liability, but an opportunity for gain, be it physical, emotional, or financial.

Ransom it. Many of the problems associated with kidnapping evaporate when the target is already dead. But things can still go wrong, as Charlie Chaplin's postmortem kidnappers discovered. They grabbed him in 1978, two months after his death, and demanded $600,000 in ransom. They didn't get it. First, Chaplin's lawyer chewed their ransom demand down by half. Then the cops arrested the plot mastermind, a 24-year-old unemployed auto mechanic named Roman Wardas, as he phoned in the ransom drop instructions. The intrepid officers had staked out all 200 phone booths in Lausanne. Mr. Chaplin has since been reinterred into a much more secure final resting place.

Display it. While shooting an episode of The Six Million Dollar Man in 1976 in a Long Beach, California amusement park, the crew accidentally knocked the arm off a figure in the funhouse. Only it was no dummy, but the wax-covered, embalmed body of Elmer McCurdy, a train robber shot by a posse in Oklahoma in 1911. His body had been claimed by a carny operator posing as his brother. McCurdy's corpse had been on the carny/county fair circuit ever since. His final owner had purchased him from a defunct wax museum thinking he was getting an ugly wax-coated papier-mâché dummy.

Sell it to science. Back in Edinburgh, Scotland, in the 1820s, snatching bodies to supply anatomy classes was a lucrative calling. William Burke and William Hare dealt in some of the finest specimens, fresh and unmarked. But they cheated. They'd started innocently enough by selling a lodger in Hare's boardinghouse who'd died owing back rent. But they promptly advanced to smothering boarders who were merely ill, and then graduated to "burking" (as it became known) any loser they could lure off the streets. They killed 16 victims before a neighbor spotted one of their fresh products. Hare got off by testifying against Burke, who was hanged and publicly dissected.

Turn it into raw materials. Human skin can be tanned. The most legendary collector of these grisly knickknacks was Ilse Koch, wife of the Buchenwald concentration camp commandant. Camp inmates with unusual or fetching tattoos had notoriously low life expectancy in camp. Koch's favorite lampshade reportedly featured a tattoo with the words "Hansel and Gretel." However, the appeal of human leather transcends Nazi Germany. The skin of the aforementioned William Burke was tanned and sold for souvenirs. William Roughead, the dean of Scots crime writers, proudly described his piece as like "an old brown leather strap." Even Charles Dickens may have owned a bit.

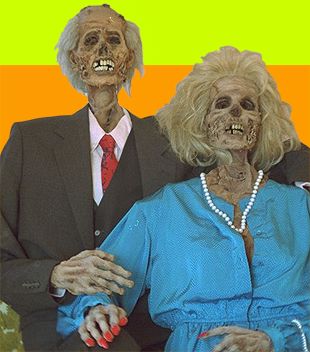

For company. The lingering corpse, covertly kept around the house for years by grieving relatives, is a staple in compendiums of wacky news items. But far more honest was Dr. Martin Van Butchnell. When his wife died in 1775, he came clean. There wasn't going to be a funeral. He loved his wife and made no secret of his plans to keep her around. He subjected her body to the then exotic practice of embalming and installed her in a glass case in the sitting room of his London home. The event was publicized nationally. Hundreds of people dropped by to visit the late Mrs. Van Butchnell until the doctor restricted gawkers to those introduced by a mutual friend. Mrs. Van Butchnell was removed from her place several years later when the doctor remarried.

The other 96? We'll leave those to your imagination.

John Marr is a freelance writer and the editor of Murder Can Be Fun.