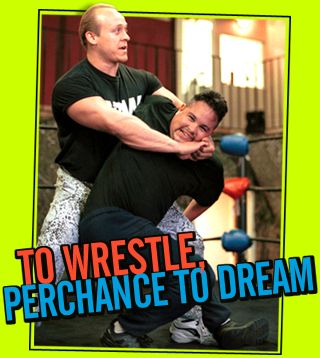

Larry Harvey weighs in at 348 pounds. Although he's hardly svelte, you wouldn't really call him a fat-ass either. Were this Alabama, rather than P.C. California, he would be known as "one big sumbitch." But despite his size, Larry runs the 1.5 mile course with the rest of his class at wrestling boot camp, and makes it through the calisthenics that follow without puking all over the concrete. Not all of his classmates can make the same claim.

Now, watching some poor schmuck spew Chef Boyardee Chili Mac has always been one of my favorite activities. But it's nothing compared to watching Larry -- who seems at least as big as my 1995 Saturn SL1 -- perform midair flips over another guy kneeling in the ring. For the record, I found myself filled with a ghoulish desire to see Larry fuck up and crush the guy beneath him. Now that's entertainment. Unfortunately (depending on your perspective, I guess), it never happened.

Larry is one of 32 students in All Pro Wrestling's (APW) winter '99 boot camp, a program for wannabe grapplers that promises to teach them the ropes of pro wrestling. The program has grown to be one of the more successful ones in the country, sending several wrestlers to the ranks of the ECW, WWF, and WCW.

These students come to Hayward, California from all over the country because they want to be pro wrestlers, and they want it bad. To that end, the boys are spending their evenings at APW learning how to take "bumps" and scrubbing toilets. (Part of APW's program consists of "breaking down" their students' egos à la real boot camp. This breakdown, as far as I can tell, is accomplished by belittling students and having them perform menial cleaning duties.)

Flipping Out

On their first night in the ring, head instructor Michael Modest is showing the guys how to tumble across the mat without getting hurt, yet make it look like it does hurt. Some of the stuff seems...well...obvious: "If you make your body round, you'll roll better." But it's a tricky balance. As one of the trainees told me, "This shit ain't as fake as people think. You got to know what you're doing or you're going to get hurt, or hurt somebody."

As Modest critiques his students' efforts, he (from a standing position) jumps up, does a flip in the air, and lands flat on his back in the ring. Rings, by the way, are not nearly as flexible as they appear on TV. The one in Hayward is little more than a piece of pressboard with canvas stretched across the top. I pounded on it with my fist, and it hurt me (of course, I'm a wuss). Modest tells his class that they too will be performing this feat before the night's over, and from the top rope of the ring no less. Eyes around the room widen. "Hell yeah," I think, "I'm going to see somebody get their neck broke!" Again, no such luck. But the flips and bumps on the mat do look painful. And pain, like vomit, is entertainment enough for me.

So why do people put themselves through this crap? Why would otherwise (partially) reasonable people subject their bodies to torment and their egos to the aspersions of moderately successful, minor-league grapplers? Why hasn't Mr. Blassie Goes to Washington received the critical attention it so richly deserves? Because we're talking about wrestling, and if you want to make it to the big leagues, you have to pay your dues. (And, of course, because nobody has actually seen Mr. Blassie Goes to Washington.)

The Program

APW grew out of Roland Alexander's efforts to start his own wrestling league in 1991. He started wrestling boot camp in 1994 after failing to find the talent he needed to book and promote shows. "I've always wanted to do something with wrestling," Larry says. "I always wondered if I could do it. Finally, my father bought his own business and hired me. So now, I have the time and the money. I'm not one to walk out once I've paid, so I'm going to make it happen."

And it does take a chunk of cash. Six thousand bucks, to be exact. Looking around the gym, at the menagerie of Blassies-to-be, I can't help but wonder where some of these kids come up with the dough. And they are kids; most of the enrollees are in their late teens or early 20s.

There's Jimmy Stultz, a 19-year-old from Indiana in his seventh month at boot camp. Like a few others in the program, Jimmy went to another camp first, but was unhappy with his training there and came to APW to be reeducated. "It's tough being out here in California at 19 with no family," he says after a session of throwing "flying arm grabs" in the ring (or maybe it was "flying arm drags," it's hard to be sure about these things). "My mom didn't believe me when I said I was going to do this. My parents are real supportive, but being all the way out here can be hard."

Jimmy's not what I was expecting when I came to APW. In addition to wrestling school, he's also taking acting and modeling classes. He's smart, funny, and soft-spoken. In fact, Jimmy's exactly the opposite of what I was expecting from these guys. "Goons in tights," I thought, "I'm gonna talk to loud, obnoxious goons in tights. Sweet." There certainly are goons around, one of whom, "Boom-Boom," yelled at me on my first night there, shoving me out of his way so that he could have unobstructed passage through a doorway. This was especially traumatic for me due to the aforementioned wussiness. But Donovan Morgan is more typical of the people I encountered at APW.

Donovan Does Dark Matches

It's easy to forget that wrestling is first and foremost a business. Donovan is a professional. By that I mean, yes, he gets paid to wrestle and to teach others how to wrestle. But moreover I mean he -- like Alexander, Modest, and some of the other instructors -- has a completely professional attitude toward the program. And like Jimmy, he's a nice guy, soft-spoken, and smart. Not to say that he doesn't put his students through their paces, or criticize them when they fuck up, but he's personally charming.

Donovan is the very model of a modern major wrestler. He's buff, Clorox-blond, fast-moving, and, when he needs to be, intimidating. He signed on with APW four years ago as a trainee. Today he helps run the program, booking gigs, promoting, and actually getting into the ring to wrestle.

What's more, Donovan has actually been to the show.

Donovan, along with Mike Modest, has wrestled "dark matches" in the WWF and WCW. These are untelevised matches performed in arenas before the main events to get the crowd pumped. Think of them as tryouts. He has had two of these since February of last year. He's on the cusp.

"Everything you've ever dreamed of happens in five minutes," says Donovan, describing the experience. "I was nervous until I came out of the curtain. But the way I looked at it was like, 'If I screw up, then I'm not meant to be here,' and that took the pressure off. The eleven minutes I wrestled on [WCW's] RAW were the most fun eleven minutes I've ever had.

"To be honest, I'm more nervous when I wrestle in a high school. The fans are so much closer, almost in your lap. They can really get to you," he continues, "especially when they start throwing stuff."

And high school shows are APW's bread and butter. They put on semipro matches wherever they can: fairs, high schools, soccer arenas, even in their own gym. And the reality is that for the overwhelming majority of these guys, high school gymnasiums will be the peak of their wrestling experience.

Hell, most of them won't even achieve that. Usually no more than a handful of guys makes it through the first round of boot camp, a four-month program. In the last two camps, eight out of 40 and 11 out of 29 actually completed the program.

When camp began, the students lined up around the edge of the ring, introducing themselves and explaining why they came. For most, pro wrestling has been a dream since childhood. Most of them won't make it as far as Donovan Morgan or Mike Modest (or even Jimmy Stultz and Larry Harvey for that matter). For many of these kids, this will be their first dream to die, and they'll have to go back to whatever bumblefuck they came from with their hats in their hands. But a select few will make it; they will be pro wrestlers. And that's enough to keep the dream alive for everyone else. And as for the ones whose dreams must die, well, like vomit and pain, that shit's pretty fun to watch too.

Mat Honan wrestles with his conscience, decisions, and breakfast cereals... but never, ever with other people.