Whatever happened to the Art of Noise? Didn't they do "Peter Gunn" sometime in the '80s? Hasn't everyone heard enough of "Moments in Love" by now? They may have invented drum and bass almost by accident twenty odd years ago, but what has the Art of Noise done for us lately?

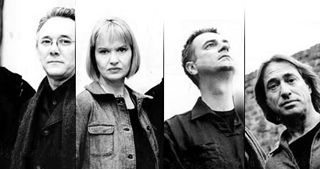

It's easy to condemn them as a novelty act whose moment has long passed. First the musicians squabbled with the Svengalis, splitting the team to make scarcely a murmur from then on. In the years since, the men with a mission, Trevor Horn and Paul Morley, were wooing back the heart of Anne Dudley (on keys), luring 10cc's Lol Creme out of retirement, and assembling the vocal stylings of a rapper (Rakim), a soprano (Sally Bradshaw), and a quietly-spoken thespian (John Hurt). All this strictly in order to celebrate, one last time before his hundred years run out, the man who "set the 20th century on its way," Claude Debussy.

On the eve of their five-date proof-of-concept tour, I cornered the band's wordsmith and ideologue, Paul Morley. What do you say to the man who sold the world a Frankie Goes to Hollywood T-shirt? Why, you talk about that most millennial of topics, bringing back the dead. But of course.

GETTINGIT: How long has the Art of Noise been back together again?

PAUL MORLEY: Well, for the first half of the '90s, you know, the Art of Noise existed as a no-tête. It still existed, but there was nobody in it. And then Anne and Trevor kind of were working on other things, and we just thought well, if we have a really good idea, we'll give it a shot. We wanted to do something, you know, with a lot of class, a lot of noise, a lot of padding, lots of art for the sake of it. We wanted to do something really beautiful.

GI: Why the classics? Why now?

PM: Well, we came to Debussy simply because we like the hundred-year parallel. And we did want to try some weird summary of 20th century music, and Debussy provided the best door to go through, because anything -- Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, you know, Charlie Mingus -- is going to be influenced by Debussy, and then therefore pop is. Pop came from jazz, as did things like Steve Reich and Brian Eno, and we just thought by going through that, we might be able to achieve this ridiculous and splendid goal of summarizing 20th century music in an hour. And why not? Nobody else would.

GI: What are you actually doing on stage, apart from indulging in metaphor?

PM: Me, personally? I'm the host. Sort of like a cross between Bez out of Happy Mondays and William Burroughs. I'm the cheerleader.

GI: So you've got yourself some maracas?

PM: I've got a hammer and a spanner, and I'll bang this spanner with a hammer. I'm like a fan of the Art of Noise who's represented by being in the group. That's my role.

GI: You're not going to be the singer, then?

PM: A band like us, you know, we don't have a lead singer, so we can choose whoever we want. And there's lots of other groups like that, like Massive Attack. There's this whole group of girls who are always chosen to front the male groups that have no lead singer. And we thought it might be very interesting, instead of going down that road, to use a classical singer. Because in a funny sort of way, that's really what they're after. Big, plain, pure grandeur. You know, a great sort of eroticism. And there's nothing purer than a great classical singer that's singing Paul Verlaine or Arthur Rimbaud.

GI: Speaking of writers, you've got a new book yourself.

PM: Yeah, it's coming out. It's called Nothing.

GI: So that's sort of like the theme right now, the no-piece group moving on to nothing.

PM: Yeah, that's right, yeah. Always repeat your best tricks, you know.

GI: So what's the book about?

PM: It's about suicide. My father killed himself 22 years ago, and it sent me off on a really strange journey. I tended to get very excited about things like Joy Division and Magazine, and that kind of intellectual side. In a way I was sort of racing away from my father's suicide. I was going to escape.

GI: So it must have affected you a lot when Ian Curtis killed himself.

PM: Yes, it did, and that's the funny thing, because I tended to pay more attention to Ian's suicide than my father's. In a way, I used him as a symbol to get through all this kind of crap. And it was all in the songs, you know, Ian was predicting his death in the songs. So I used that for a long time as a way around this blockage. The book actually begins with Ian, and then gradually he is replaced by my father.

GI: So that's basically the entire subject? I heard it was about death.

PM: It's about death, yeah. It's in five parts. It's five ways of approaching the same thing. In a way suicide is a strange kind of death, because it's not really a death, but it's more than a death. There's this weird factor involved in it, you know. But within the pattern of the book there's a lot of contemplation about death. There's a few jokes in there.

GI: Well you'd hope! The other big book on suicide is Savage God by A. Alvarez. That's got a lot of jokes in it.

PM:What I wanted to do, in a funny sort of way, is write a book about suicide that's infused with the last 30 years of pop culture, because Alvarez wrote that book in the early '60s, and so much has happened since. So many suicides, you know. Kurt Cobain and that kind of whole blah thing. So I wanted to just do a weird kind of coda from the point of view of someone who was a punk rocker, someone who lived in pop culture, and who was, you know, on that side of things.

GI: A lot of people who've had suicide occur in their lives, you know, there's a dramatic pull. Have you felt sort of like that something nagging at your heels yourself?

PM: In my particular instance, I got self-conscious about it to such an extent that I see it coming time and time again. I actually did try when I was a teenager. There I was playing Peter Hammill, not knowing that my father -- I just thought he was a Dad, you know, a balding man -- was really suicidally inclined and was heading towards it. In the same year as "Anarchy in the U.K." and the Sex Pistols, he really did spit in the face of God. He killed himself. I was paying so much attention to punk rock and there was my father taking rebellion seriously. So it was kind of an interesting parallel there. I was so obsessed with punk rock that I didn't really see what was going on around me.

GI: Now they're all doing the 20 years on reunion tour with everybody out there looking a lot fatter.

PM: Fat and forty, yeah, and I'm a fine one to talk. I mean, I'm the man who told Mick Jagger to his face when he was 33 to shove it. But it's the classic case with the Art of Noise: You suddenly realize that your watch has stopped, you know. You find it might be a little bit embarrassing around the edges, jumping about like a maniac on stage, but somehow it just seems to be: Why not? So long as you keep reforming and redoing. But who wants to see The Human League do "Don't You Want Me" 20 years on? Breaks my heart.

GI: But you will be doing "Peter Gunn"?

PM: Oh my God, do we do "Peter Gunn." But we do it as a little commentary on our own selves. You know, if we didn't do "Moments in Love" it would probably look a bit strange.

GI: Is this the beginning of a big comeback, then?

PM: We're kind of just doing it to see. Because, you know, these four individuals, the last thing on earth we would want to be is in a pop group, man. We have been in a pop group before. Many, many years ago. Lol's been having it since 1938. And now, it's very awkward to be in a pop group at all.

GI: It's a bit strange digging up Lol Creme, isn't it?

PM: The thing I like about Lol Creme and Kevin Godley in 1975 is they went out to make a triple album called Consequences, took two and a half years to make it, and when they came out of the bunker thinking they'd made their masterpiece, punk rock had happened. No, Lol was good, because everyone was onto us to hire someone new and exciting and lower the average age of the group so we decided to get someone older and raise the average age of the group.

GI: Sure, he makes you not the oldest man on stage, for a start.

PM: Well there's that.

The Seduction of Claude Debussy is available in fine music stores across the globe. Paul McEnery is still two years shy of fat and forty. Dammit.